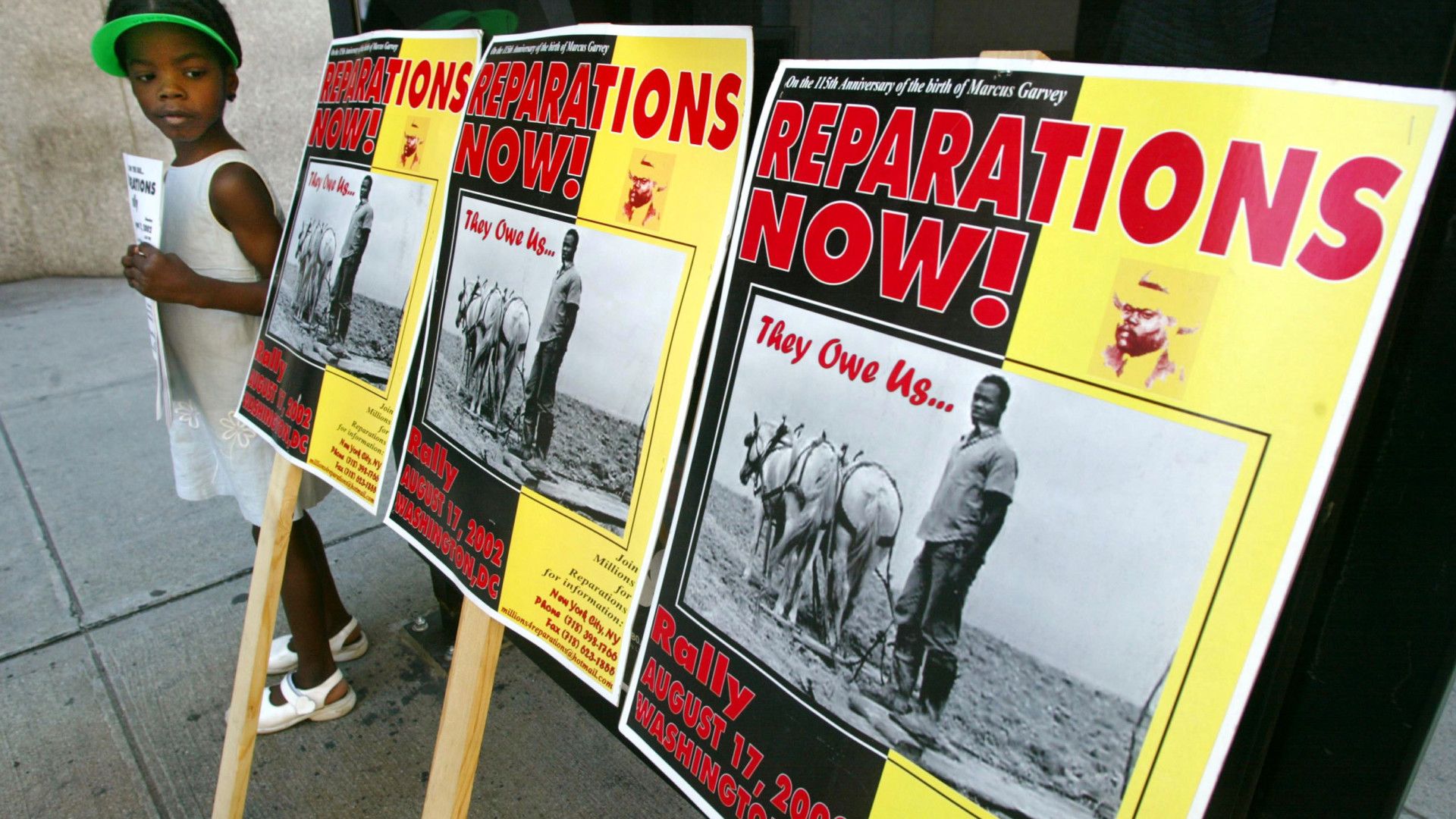

Like clockwork, the issue of reparations for descendants of U.S. slaves surfaces every presidential election cycle, and it’s back on the campaign agenda in 2020.

To be sure, mounting scholarly research and aggressive community activism has made it increasingly obvious to many Americans that the nation’s history of slavery and racism continues to adversely impact black Americans.

No less an authority than the Federal Reserve found in a recent Survey of Consumer Finances for every dollar owned by the average white American family, the average black family has just 10 cents, adding fuel to arguments that African Americans continue to suffer from historic discrimination.

The discussion tends to be confined during off-election years to obscure academic lectures or barber shop debates about the unlikely future of reparations. But it has evolved into a wider, series of public conversations about the possibility of it actually happening. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 essay in The Atlantic contributed to the discussion, pushing the topic into the purview of deep thinkers and mainstream media pundits. The New York Times’ conservative columnist David Brooks flipped his argument and came out earlier this month in support of reparations on the newspaper’s editorial page.

Inevitably, the flurry of attention over reparations wended its way this year to the campaign trail. The growing cast of candidates is an exceptionally diverse group which so far includes two African Americans, Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Kamala Harris (D-CA). Both are making a pointed effort to court black voters, who this year have greater influence over the primary process, even while campaign-tracking reporters pose questions that went largely unasked in previous campaigns.

Many of the declared Democratic candidates feel compelled to offer varying degrees of support for reparations. When they do, they choose their words with the utmost caution, at the risk of alienating a vital constituency needed to win the nomination, or offending a broader group of voters required to win the general election.

Several of the announced candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination have offered measured endorsements for federal studies of reparations or have backed broad, race-neutral programs that would benefit all Americans, but that have the unarticulated goal of assisting black Americans. They are tip-toeing through a minefield energized by an activist, hard-left, which is demanding answers to long-ignored concerns about racial equity, police brutality, unequal housing and education policies and other social concerns that disproportionately harm black Americans.

So far, the candidates expressing views on reparations include:

- California Sen. Kamala Harris: Harris said on the nationally broadcast radio show “The Breakfast Club,” that the federal government should pay black Americans to address the legacy of slavery and discrimination. She repeated that view in an interview with The New York Times. “We have to be honest that people in this country do not start from the same place or have access to the same opportunities,” Harris said. “I’m serious about taking an approach that would change policies and structures and make real investments in black communities.”

- Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren: At a CNN town hall meeting this week, Warren endorsed House legislation aimed at studying reparations for families of formerly enslaved black Americans. She declined, however, to promise support for direct payments. “This is a stain on America and we’re not going to fix that, we’re not going to change that, until we address it head on, directly,” Warren said. “And make no mistake, it’s not just the original founding. It’s just what happened generation after generation.”

- Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro: In repeated media interviews, Castro has called for reparations, including earlier this month on CNN’s State of the Union. “If under the Constitution we compensate people because we take their property, why wouldn’t you compensate people who actually were property?” he asked.

- New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker: Offering a “baby bonds” plan as the cornerstone of his campaign platform, Booker proposes creating a federally backed savings account for all U.S. children. He argues that his program wouldn’t be exclusive to black Americans, but would be a form of reparations because the money provided would be disproportionately passed along to poor African American children. “It’s certainly accurate to see to see the baby bonds legislation as a form of reparations through that lens,” said Booker spokesman Michael Tyler told National Public Radio.

- Former U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke: — While campaigning in Iowa, O’Rourke acknowledged enjoying “privileges” as a white man in America not afforded to black Americans, and voiced support for a study looking into ways to make society fairer. “As a white man who has had privileges that others could not depend on, or take for granted, I’ve clearly had advantages over the course of my life,” he said recently on NBC’s Meet the Press. “I think recognizing that and understanding that others have not — doing everything I can to ensure that there is opportunity and the possibility for advancement and advantage for everyone — is a big part of this campaign and a big part of the people who comprise this campaign.”

- Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar: Stopping short of endorsing monetary reparations, Klobuchar told reporters that her preferred approach would be to make federal investments in “those communities that have been so hurt” by slavery and racial discrimination. “It doesn’t have to be ‘direct pay’ but invest in communities hurt by racism,” she said on Meet the Press.

- Writer and lecturer Marianne Williamson: Unquestionably the most outspoken advocate for reparations, but also among the least known candidates, Williamson has outlined in her presidential platform an ambitious plan to spend $10 billion per year over a 10-year period on reparations for descendants of enslaved African Americans. “I believe $100 billion given to a council to apply this money to economic projects and educational projects of renewal for that population is simply a debt to be paid,” Williamson said in an interview with CNN’s New Day.

- Sen. Bernie Sanders: As he did during his 2016 presidential primary campaign, Sanders has declined to support reparations. He says, however, that he favors federal policies that would help distressed neighborhoods — an approach he said would be of particular benefit to black communities. Pressed about his position during a CNN town hall, Sanders questioned the idea of reparations, in general. “What does that mean?” Sanders said in response to Wolf Blitzer’s “up-or-down” question about his position on reparations. “What do they mean? I don’t think anyone’s been very clear.”

Sanders’ comments faintly echo statements he made during his previous presidential nomination run, when he described discussions over reparations as “divisive” and dismissed as impractical efforts to get it passed. Asked directly during a 2016 televised interview with Fusion, if he would support legislation as president to provide reparations to black Americans, Sanders flatly rejected the idea:

First of all, its likelihood of getting through Congress is nil. Second of all, I think it would be very divisive. The real issue is when we look at the poverty rate among the African American community, when we look at the high unemployment rate within the African American community, we have a lot of work to do.

So I think what we should be talking about is making massive investments in rebuilding our cities, in creating millions of decent paying jobs, in making public colleges and universities tuition-free, basically targeting our federal resources to the areas where it is needed the most and where it is needed the most is in impoverished communities, often African American and Latino.

His more recent brittle response during his CNN town hall may have shown him to be the most reluctant supporter of reparations among the Democratic hopefuls, even if his response was refreshingly candid. It also underscored the absence of a consensus as to what reparations policy looks like, or more practically, or how such a policy could be achieved.

With the exception of the long-shot Williamson campaign, none of the Democratic candidates who have spoken about reparations have done so in a way that would exclusively target black Americans. Instead, reparations-friendly candidates — specifically Booker, Harris and Warren — say they want programs that are universal in approach, not just for a set of policies or programs that benefit black Americans.

However, reparations supporters — most prominently, the American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) movement, a largely online group — demand that political leaders target their efforts to obtain reparations exclusively for descendants of slaves. According to the ADOS website, its agenda calls for “set-asides for American descendants of slavery, not ‘minorities,’ a throw-away category which includes all groups except white men.” But even among supporters for reparations, there’s debate about whether reparations should be exclusively for black Americans who can credibly trace their ancestors to U.S. slaves.

Frank Newport, a senior scientist with Gallup, noted in a recent issue brief that “the term ‘reparations’ is a little like ‘socialism.’ It means very different things to different people.” And support among black Americans — as well as a lack of support among most white Americans — for reparations is neither unexpected nor universal. “Overall, blacks in the U.S. have continuing concerns about discrimination and structural impediments to their success, and most believe that the government must step in and do more to help this situation,” Newport wrote.

“The concept of reparations per se is broad, and the exact level of black support for the idea depends on how it is defined. But we know that at least a majority of blacks appear from past polling to be in favor — not surprising given the general context of black support for the government actively addressing race inequalities in the U.S. today.”

As columnist Perry Bacon recently noted on FiveThirtyEight, reparations is a “very controversial idea” — that is to say, a deeply unpopular one — with the American public. “A July 2018 survey from the left-leaning Data for Progress found that 26 percent of Americans supported some kind of compensation or cash benefits for the descendants of slaves,” Bacon wrote. “A May 2016 Marist survey also found that 26 percent of Americans said the U.S. should pay reparations as ‘a way to make up for the harm caused by slavery and other forms of racial discrimination.’”

To her detriment, Harris discovered recently that expressing an opinion on reparations, even before a predominately black and supportive audience, can be risky. While attending the recent Power Rising 2019 conference in New Orleans, where she spoke in support of reparations, Harris sat for a video interview with the black-oriented website The Grio. She cited her support for the LIFT Act, an ambitious tax plan and cash income program targeted to provide $500 monthly to working families and single people. Pressed during the interview about how it would exclusively help black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved several generations ago, Harris balked.

“So, I’m not gonna sit here and say I’m gonna do something that’s only gonna benefit black people,” Harris said. “No. Because whatever benefits that black family will benefit that community and society as a whole and the country, right?”

Harris’ response didn’t sit well with ADOS activists, who took to social media outlets in outrage and insisted they wouldn’t allow any Democratic presidential candidate to dismiss their concerns. Stung by President Barack Obama’s failure to embrace reparations during his two terms in the White House, ADOS co-founder Antonio Moore pledged this election cycle will be different. “We will not go through what we went through with Obama,” Moore told The Grio in response to the Harris interview.

Kamala Harris got flustered during Grio interview and finally came out and said she’s not doing anything that’s only for us. It’s understandable that she’s still so unable to stay on message. After all, we hit her so hard she thought the Russians did it!https://t.co/7wyiF5QbCc

— ProfessorBlackTruth (@ProfBlacktruth) February 27, 2019

The heated debate over reparations is nothing new. Going back to the closing days of the Civil War, Gen. William T. Sherman issued a “Special Field Order 15,” granting captured land from white slaveholders to freed enslaved people. Sherman recognized that freeing people from bondage should be only the first step. The Union promised every emancipated African American a parcel of land and a means to provide for themselves, birthing the phrase “40 acres and mule,” which became the freedman’s claim to a stake in the nation’s life.

Of course, such a policy was never enacted. In the ensuing centuries, black Americans suffered a series of racial setbacks from Reconstruction to legalized segregation to institutional social and economic racism.

Calls for reparations went unheeded, including those by former Rep. John Conyers, a Michigan Democrat, who introduced a bill into every session of Congress for decades before his 2017 retirement, demanding the federal government “study and consider” how to give reparations to black Americans for the harm committed during slavery. Conyers’ legislation languished, receiving a hearing only in 2007 and never advancing further. Current House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) has expressed support for the legislation, now sponsored by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) along with 35 co-sponsors.

William “Sandy” Darity, the Samuel DuBois Cook professor of public policy at Duke University, said the current interest in reparations suggests it’s a movement that may last beyond the current political season. He said in an interview with Think Progress that if Congress forms a commission to seriously study past historical wrongs endured by black Americans and makes the case for correcting them, then reparations would become a reality.

“I certainly don’t think that could happen now, but with a change in the composition of Congress in 2020, which isn’t that far distant, then there is a path that can be charted for reparations,” said Darity, who has discussed various reparation proposals with some of the Democratic hopefuls. “I think it’s a risk that has to be taken,” he added. “Real political leadership,” he said, “requires people to encourage the American people to do the bold things that need to be done.”